The Musical Legacy of Brahmanbaria – II

Posted by bangalnama on January 23, 2009

(Continued from Part 1)

Of the musicians that hailed from the illustrious Bajaina Bari (House of Music) of Shibpur, Brahmanbaria, and the Seni-Maihar school, Alauddin Khan was undoubtedly the most influential. He lived for 110 years, played over 30 instruments from the string, wind, bow and percussion groups, was a master vocalist in dhrupad, dhamar and other traditional styles, composed several ragas, invented and modernized musical instruments, trained some of the most revered musicians of our times, and conceived the first ever musical orchestra in the history of Indian classical music. A larger-than-life portrait of Baba Alauddin Khan emerges from interviews and recounts given by the maestro himself and several of his students including Pandits Ravi Shankar and Nikhil Banerjee, Ustads Ashish Khan and Mobarak Hossain Khan, and filmmaker Ritwik Ghatak.

The early years

Towards the end of the 19th century, a child named Alam was born in the Khan household of Shibpur in rural Chittagong, bordering Tripura. “Ustad Alauddin Khan was my uncle”, writes Mobarak Hossain Khan. “We called him Laal Jetha. His complexion was ruddy, like raw turmeric, and hence the name, meaning ‘red uncle’.” He was an unusual child, a born vagabond, and became a musical prodigy very soon. He was sent to a Maktab to study when he was a child. But school was unattractive to the boy. He bunked classes regularly and instead, spent time in the local Kali temple, or on the ghats of the Titas, where sadhus and bauls would assemble to sing.

Before long, the mother came to know of the boy’s daily expeditions. When forced to return to school, he left home promptly and fled to Calcutta, where he would spend days on the streets, surviving on “langarkhana” lunches and sleep nights on the porch of a ‘dispensary’ (clinic) near the banks of the Hooghly river; all the while urging and looking around desperately for a guru. Soon he become a flute player in the Star Theatre, and trained under a host of musicians in the city.

“Those days, prostitutes used to sing and dance on the stage. His pay was fixed at five rupees a month. He began his musical career as a flute player in Calcutta and went to Udaipur later. He dreamt of learning the Sarod from the great Sarod maestro Wazir Khan (of the Tanseni gharana), who was then at Udaipur. In spite of his best efforts, Wazir Khan did not care to meet him. Wazir Khan used to commute from his home to the Princely court on a horse-drawn carriage. One day Alauddin threw himself on that path to obstruct his way. This was about a hundred years back, things were different then. The knowledge of music used to be a well-guarded secret which none used to share with others”Ritwik Ghatak

So recounts noted filmmaker Ritwik Ghatak, in an interview published in “Jalim Singher Journal”, Sept. ‘76-April ‘77. Ghatak reminisces in length in this interview, about his Guru of Sarod, revealing anecdotes from Baba’s childhood and later life. “That person, my Guru, was crazy. On behalf of the Sangeet Natak Academy I went (to Maihar) to make a documentary film on him. I came to know a lot of things about him then. Alauddin Saheb told these things to me. He used to love me!”

And he goes on with the Wazir Khan episode –

“I do not know to what extent you have seen those (earlier) days. I have seen but just a little. On stubborn insistence of the young man to be a pupil, Wazir Khan said: ‘Well, then be my servant.’ Alauddin Khan did his household chores, endured much hardship, and listened with a sharp ear to the maestro playing the Sarod. He was not allowed to touch the instrument. After two long years, Wazir Khan relented, accepting to admit him as a pupil. Then began the period of training. He learnt for full fourteen years. In those days, unless the Guru gave permission, no one could perform before an audience. I mean, you are simply not allowed! For example, I am not allowed. He (Alauddin) died without giving me permission, so I do not perform. I play for my wife and children only. I have stopped playing the Sarod.”

“Wazir Khan gave him the permission after fourteen years and with the permission, he went back to Brahmanbaria for a brief time. By then he was employed by the Maharaja of Maihar as the court musician of Maihar.”

The Guru

Baba Alauddin was the central figure in his gurukul (school) in Maihar. Pandit Nikhil Banerjee, in his essay “My Maestro as I saw Him”, talks about the gurukul practice and how Alauddin’s liberal worldview helped spread the parampara (musical legacy) beyond genetic lineage, as was a prevalent practice in gurukuls for ages:

“Gurukul presupposes that the students be in constant company and guidance of their master whom they serve in every way. It is only when the master is satisfied with the earnest and sincerity of the student, that he imparts his power and the wealth of all the realizations of his own Sadhana (practice). Between the teacher and the taught the principle of give and take is solely this – the student can only offer his devotion and service, and the teacher can let him have knowledge and truth.”Pandit Nikhil Banerjee

“Sad to say, for many many years this principle used to operate in a limited sense and the great Ustads kept up a very secretive approach. They would not let the student see the truth unless there was a blood relation between them. Baba Alauddin Khan Sahib was great in going against this current, and courageously proving that our music is not a hidden magic but essentially a matter of practice aiming at self-realization. He was not a musician by family tradition. His life is quite a classic story of endless tests and trials through which he found his way towards knowledge and enlightenment. It is probably this background which bred such a strong antipathy towards anything mean and narrow in the sphere of teaching. He was a teacher incarnate. Any student, if really deserving, had from him the shower of his blessings and by the sheer touch of his genius, felt quite transformed.”

Alauddin was also guru to his grandchild Aashis Khan (son of Ustad Ali Akabar Khan), and excerpts from an interview by Ustad Ashish Khan reveals one of the most intimate stories of tutelage, passing of a musical lineage from a grandfather to a grandson:

The beginning: “I was very young when I was given a baby sarod. Probably 5 or 6 years old. This baby sarod was given to me by my grandfather, and he started teaching me. He would draw lines on the sarod plate so that I could put my finger in the right spot. At first it wasn’t that many hours but gradually it stretched to 12 hours a day – 4 in the morning, 4 in the afternoon, and 4 hours in the evening. Plus, he would teach me whenever he would feel like – sometimes in the morning, sometimes in afternoon, even during the night. I used to practice in his bedroom, or in the big sitting-cum-living room, so that he could hear me and correct me. That way I was always under his guidance, I was protected.”

The early taalim: “To begin with it was only simple exercises. No raag, or raaginis, no compositions. Just exercises, to develop the right and the left hands. First it was alaankars and bols, and then there was a stage when he started to show me meend (bending) because meend can only be practiced when the ear is fully developed. But before that, you have to be able to play correct notes, and all shuddha swaras (natural notes), no komal swaras (sharp tones), nothing. This went for a few years. Then he started giving me gats (compositions). It used to be Raag Bilawal during the day. In the evening it was Yeman Kalyan. This went on for another few years. He never changed the raagas, never gave new materials. Unless I perfect the exercises to his satisfaction, he would never give me a new lesson. If I couldn’t play the old lesson, how could I pick up a new one?”

Ustad Ashish Khan

Coming of age and the first concert: “Once I perfected the early lessons, after some time, as I became more matured, he started pouring things. My God, I was so overwhelmed, it was too much for me to digest. Because I was so young. I was eleven, twelve. Sometime I used to hate it, because it was so rich, so complex, and so difficult to be able to differentiate between raagas, for example the three raagas – Puriya, Sohini, and Marwa! Same with the trio of Hamir, Kamod, and Chayanat! They were so very related, with subtle borderline differences. Raagas from these families were very difficult for me to absorb, to memorize, and to be able to digest. So that is how my taalim went, on and on for years.”

“Then at twelve or thirteen, I played with him in New Delhi on All India Radio. A national radio program, in a live broadcast. Tabla was played by late Pandit Kanthe Maharaj, the Guru and Father of Kishan Maharaj. That was a great experience for me.”

The Man

In the preface* to Alauddin’s autobiographical book “Amar Katha” (My Life), Pandit Ravi Shankar writes fondly about his guru.

Pandit Ravi Shankar

He was a bookworm – a regular subscriber to the contemporary “Bharatbarsha”, “Prabashi”, “Basumati”, “Sangeet Prabeshika”, as well as Hindi magazines like “Maya”, “Manohar Kahaniyan” etc. He used to read practically any book he could lay his hands upon. Baba had a strict policy of not receiving any gifts from his students. However, Ravi Shankar and other disciples soon figured out that books, magazines and journals were exempt from his list of forbidden gifts! Baba had indeed a broad spectrum of reading: “Shei Quran, Gita, Ramayan, Mahabharat, Bankimchandra, Robi Thakur theke shuru kore Dasyu Mohan series, ittyadi detective lekha ebong bat-talar boi kichhui tini bad diten na.” (He didn’t leave out anything – starting from the Quran, Gita, Ramayana, Mahabharata, classics like Bankimchandra, Tagore, all the way to the detective tales from “Dasyu Mohan” series, even Bat-tola booklets. He read everything!) Reading and gardening were his most loved pastimes, when he was not engrossed in riyaz or teaching.

Pandit Nikhil Banerjee also paints a candid picture of Baba’s life in Maihar, in his memoir-essay:

“While staying at Maihar Baba gave as a life-style very much like that of an Ashram or hermitage. As a person he was simple, unassuming and completely devoid of egoism. He lived a life with the minimum of necessities and always helped himself to the best of his physical abilities. He had a strong aversion towards any kind of luxury. Maihar is a place of extreme climate and it becomes unbearably hot during the summer because of the limestone factories that surround it. Once, his son Ustad Ali Akbar Khan Sahib bought an air-cooler and took it to Maihar with the expectation that it might give him some relief. After a few days it was rejected with scorn. As long as his health permitted him to move, he would wash his own clothes every day and would go to the market to buy his daily necessities and not let the students go there and waste their valuable moments of practice.”

“While staying at Maihar Baba gave as a life-style very much like that of an Ashram or hermitage. As a person he was simple, unassuming and completely devoid of egoism. He lived a life with the minimum of necessities and always helped himself to the best of his physical abilities. He had a strong aversion towards any kind of luxury. Maihar is a place of extreme climate and it becomes unbearably hot during the summer because of the limestone factories that surround it. Once, his son Ustad Ali Akbar Khan Sahib bought an air-cooler and took it to Maihar with the expectation that it might give him some relief. After a few days it was rejected with scorn. As long as his health permitted him to move, he would wash his own clothes every day and would go to the market to buy his daily necessities and not let the students go there and waste their valuable moments of practice.”

“He practised austerity in his own life and had therefore the right to impose it on us. He was a disciplinarian and would never allow the slightest deviation from his ideals of simple living, strict observance of Brahmacharya during our stay at Maihar, a total withdrawal of the mind from all kinds of superficialities, directing all the energy to practice of music and concentration. In going to enforce all this he had to keep up a certain hardness which was, in reality, a show. Stories of Baba’s severe scoldings, beating with the bow of violin and throwing of tabla hammer are so common that people are sometimes terribly mistaken to assume that he was a kind of an old village schoolmaster lacking in any sophistication, with only the ability to be rather ridiculously stern. But this image of himself he deliberately projected in order not to allow any liberty to the disciple. He always had the tension that soft treatment on his part would only spoil them. One day I heard him speaking out rather candidly, “Don’t you see that I am a grandsire? Don’t I feel like taking them (meaning his grandsons) in my arms-patting and loving them. But I am afraid it may spoil them.” Here was the inner voice which could be heard seldom or never. Beneath the veil of toughness was the soft and tender soul bubbling with humanity.”

“We used to watch with wonder how in different corners of his premises he arranged to set up wooden pieces of shelter-racks to let the birds build up their nests. At the time of his meals these birds would gather around him and he enjoyed their company. Whenever any Sadhu or saint was around, Baba would give him God-like treatment, offering food and clothing. He used to clean with his own hand the left-overs of their food and never let us touch them.”

“I cannot resist the temptation to narrate a couple of episodes which reveal Baba’s humanity.”

“Once in the market at Maihar he watched a person sitting out rather dejected in a corner with a number of dholaks (folk drums) to sell but not heeded by anyone. He was touched so much so that he took up one dholak and started playing. The result was obviously a crowd around him. Many of them were throwing coins and a few dholaks were sold out within a short time. Baba saw that some money were collected. He gave it all to the dholak-seller and went home happy.”

“About religion Baba was very broad-minded. When he used to have his daily prayer or Namaz, he would ask me to go into my room and have my Gayatri Yapa. Some of the habits and practices he suggested got so firmly riveted into my mind as mantras or sermons. He would say, “Whenever you are giving a performance, meditate on your Guru first and then you will see that he takes you over and carries you through. Whenever you play a Raga, begin with worshiping and welcoming it. Imagine it to be deity. Bow down and pray that it should have mercy on you and it should become alive through your medium. Never approach a raga with a feeling of pride or vanity in your heart. Music grows out of the purest feelings of your soul and hence the mind of the musician, if only purified, can produce the vibration.” Baba’s behavior on the stage sometimes became rather erratic. But this was only the result of a certain tension and apprehension that he might fail to establish the raga. I saw him many times uttering Namaz and even crying out “Ma, Ma” to Goddess Saraswati. This appeared strange to people. But I had the most glorious experience to hear the same person playing surasringar to himself in Maihar with all the serenity and calm of mind. I still remember that after a couple of minutes it seemed too much for me. The emotional appeal was so tremendous that my entire being was gone to pieces, senses suspended and it was a trance all over. Anyone who heard him there could realize how great a Naad (sound) Yogi he was.”

The Band

Legend has it that after an epidemic (’red-fever’ according to popular consensus, Mobarak Hossain Khan calls it plague) Baba Alauddin Khan was affected by the tragedy and with an aim to provide solace to orphaned children inducted them (with aid and enthusiasm from the ruling prince Braj Nath Singh) into an orchestral group that came to be known as the Maihar Band (1918). “Band” was a popular word in those days, because of the British. It was a symphony of different instruments, a concept that never really existed in Indian music before the British arrived. The Maihar Band was conceived as a troupe of young musicians playing indigenous instruments like the sitar, esraj, sarangi, dotara, ektara, shehnai, flute, tabla and bayan.

Legend has it that after an epidemic (’red-fever’ according to popular consensus, Mobarak Hossain Khan calls it plague) Baba Alauddin Khan was affected by the tragedy and with an aim to provide solace to orphaned children inducted them (with aid and enthusiasm from the ruling prince Braj Nath Singh) into an orchestral group that came to be known as the Maihar Band (1918). “Band” was a popular word in those days, because of the British. It was a symphony of different instruments, a concept that never really existed in Indian music before the British arrived. The Maihar Band was conceived as a troupe of young musicians playing indigenous instruments like the sitar, esraj, sarangi, dotara, ektara, shehnai, flute, tabla and bayan.

“They were motivated by the idea of having an indigenous philharmonic apart from the formal Military band that was under the charge of Alauddin Khan. Soon with Baba’s passionate teaching and dedication of the young boys and girls, there existed an orchestra that used the full range of Indian instruments with a few western ones. Baba could impart sufficient knowledge of music to these untrained children so that they handled western instruments like piano, violin and cello with equal ease. The band positioned itself in the gallery above the main Darbar hall and would play western and Indian compositions to the dignitaries assembled below. Alauddin led as the band-master. He would often exclaim that there is no equal on this earth to this classical band. In his early years of musical training in Calcutta, he had trained with the famous Indian conductor Habu Dutt as also with Robert Lobo (conductor of the Eden Garden Orchestra). His appreciation of western music was testified by the sketch of Beethoven that always hanged in his room in Maihar. During his stay in Rampur as an artiste in the court band he adopted several Dhruva-padas to orchestral compositions.”

“The young members of the band, awed by their own ability to produce the magical sound of the orchestra, mastered the skill of memorizing the compositions. According to Shri Lakhanlal Pandey, a Sitarist in second generation Maihar band, there were about 250 compositions of which some 150 bandishes are known to present members of the orchestra. Apart from some western tunes, compositions in Khamaj, Tilak Kamod (aao gori gale lag jao), Yaman abounded along with rare ones like Hemant, Bihag etc. He invented ragas like Madan Manjri, Subhavati, Dhavalasri, Hemant-Bhairav, Bhuvaneshwari, Hemant, Manj-Khamaj and Hem Bihag etc. However in orchestration he kept the compositions simple so that the children could pick them up. He was quick to appreciate the wandering minstrels and adopted folk tunes like Rajasthani Ghoomar, Mand, Baul of Bengal and folk songs from Malwa for the orchestra.”

Alauddin was an innovator. The resources in a small princely state like Maihar were limited. The palace had a grand piano; violins could be obtained with some effort but other western instruments were simply out of reach. Till the time a cello could be ordered and supplied, Baba got a sarangi made which measured twice the size of usual one. It had strings which could be tuned and using a large bow would give out a deep tone almost that of cello. He named it “Saranga”. After using Sarod in the troupe, Baba found that this melodious instrument could not be heard among others. He then set out to create a replacement which would serve his purpose. He fixed the plate and frets of Sitar to the leather base and bridge of Sarod and played it with a plectrum (Jawa). Baba also invented Chandra Sarang but could not include it in the band. It was a complex instrument with leather mounted base of Sarod, fret-less but with resonance strings, played using a bow. Another novel invention was the Naltarang, designed from barrels of different bore guns.

The members of the first Maihar band were: Anar Khan (Sitar), Vishwanath (Violin), Shiv Sahaya (Bansuri, Clarinet), Ramswaroop (Sitar, Banjo), Baijnath (Bansuri), Tansu Maharaj (Harmonium), Brinda Mali (Israj), Moolchand (Israj), Assistant Band-master Jamna Prasad/Gulgul Maharaj (Harmonium), Jhurrelal (Nal Tarang), Pt. Girdhar Lal (Nal Tarang, Piano), Lachchi Surdas (Tabla, Dholak), Sukhdev (Saranga, Cello) Pt. Urmila Prasad (Cello), Mahipat Singh (Sitar), Chunbaddi (Israj), and Dashrath Mali (Sitar, Banjo).

The Legend

As the story of his life unfolds from historical accounts, anecdotes and personal memoirs, Ustad Alauddin Khan was perhaps the single brightest luminary in the world of Bharatiya Shashtriya Sangeet. Owing to his multifaceted contributions as musician, composer, teacher, and conductor, he was hailed as an ‘acharya’ and had been referred as a ‘‘monarch in the realm of music’.

Ustad Mobarak Hossain writes, “The contemporary swarupa (identity) of classical music was created and enriched by his contribution. He also introduced Indian classical music to the western world and opened up to the west a new horizon – In 1935, he went on a global tour with the dance troupe of the great Indian dancer, Udayshankar. During this tour, Baba enchanted his audiences with the magic of his music. To the music lovers of India and other countries of South Asia, Alauddin Khan is revered as a saint and considered an institution. He is accoladed as the founder of the distinctive Sangeet Gharana, named Seni-Maihar Sangeet Gharana.”

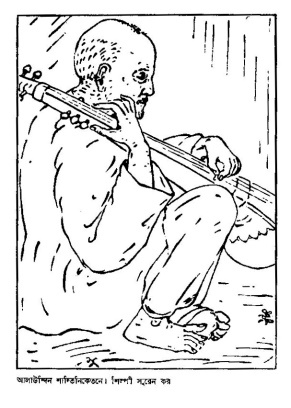

The Ustad had a penchant for creating ragas. He composed new ragas like – Hemanta, Prabhatkeli, Hem-Behag, Chandika, Rajesri, Madan Manjari, Durgeswari, Muhammad, Kaushi, Shubhabati, Umabati, Nagarjan, Bhagabati, Hemanta-Bhairab, Swarasati, Dhabalsri, Madavgiri, Megh-Bahar, Bhuvanswari, Haimanti, Manj-Khambaj, Kedar Manj, Gandhi-Bilawal and Rabindra, among others. He wrote several songs and gats and whenever he conceived any raga, he immediately scripted it down. His skill in writing lyrics was magnificent and he often used the childhood pen name ‘Alam’ for his lyrics. Baba wrote a number of books on music, too. His performances in the courts of maharajas and nawabs, as well as public performances in urban concert halls were flamboyant and grandiose, and the Ustad was honored with awards and titles, including “Padmabhusan” and “Padmabibhusan” by the government of India, “Desikuttam” by Biswabharati University in Santiniketan and the title of “Khan Sahib” by the British government.

The Ustad had a penchant for creating ragas. He composed new ragas like – Hemanta, Prabhatkeli, Hem-Behag, Chandika, Rajesri, Madan Manjari, Durgeswari, Muhammad, Kaushi, Shubhabati, Umabati, Nagarjan, Bhagabati, Hemanta-Bhairab, Swarasati, Dhabalsri, Madavgiri, Megh-Bahar, Bhuvanswari, Haimanti, Manj-Khambaj, Kedar Manj, Gandhi-Bilawal and Rabindra, among others. He wrote several songs and gats and whenever he conceived any raga, he immediately scripted it down. His skill in writing lyrics was magnificent and he often used the childhood pen name ‘Alam’ for his lyrics. Baba wrote a number of books on music, too. His performances in the courts of maharajas and nawabs, as well as public performances in urban concert halls were flamboyant and grandiose, and the Ustad was honored with awards and titles, including “Padmabhusan” and “Padmabibhusan” by the government of India, “Desikuttam” by Biswabharati University in Santiniketan and the title of “Khan Sahib” by the British government.

An important contribution of Alauddin to the contemporary musical scene was his role in the development of indigenous musical instruments through necessity and experimentation. While working with the Maihar Band, he invented the Chandrasarang and the naltarang. Besides, his contribution in the modernisation of the sarod has been significant.

Alauddin was also a noted vocalist. His skill in Dhrupad and Dhamar was unmatched. He was equally skilled in Khayal and Thumri. Though sarod was his main instrument, his command over bina (veena), behala (violin), sursringar, rabab, chandrasarang, bnashi (flute), clarinet and shehnai was unparalleled. He could also play well on percussion instruments like pakhwaz, madang, dhol, tabla-bayan, naqara, tikara, etc.

The first gramophone record of Alauddin Khan came out in 1935. These were recitals on the sarod and violin and the discs were brought out by the Megaphone Gramophone Company. Later, long-play records of these recitals were also produced.

Alauddin breathed his last in the year 1972, the end of a legendary era in Maihar. Nikhil Banerjee reminisces, “There was a very old temple on top of a hill at Maihar known as the temple of Saradamai. Pilgrims came there from far and near and surprisingly enough they would come to see Baba straight from the temple. To the poor common people of Madhya Pradesh who knew nothing about music, Baba Alauddin Khan Sahib was sort of a Sadhu-a noble soul. People of Maihar loved and honored him like anything excepting the Muslim community, who did not quite approve of his liberal views on religion. After his death they at first refused to carry him for burial. There was a storm of controversy. But at the end we saw that the burial procession was being attended by the Hindus and Muslims alike and even the chief priest of the temple of Saradamai joined. It was a marvelous spectacle! Baba can be compared to Sant Kabir whom both the Hindus and Muslims claimed to have belonged to their community. I would rather say that like Sant Kabir he was far above these social distinctions. He was a great Naad Yogi.”

The Legacy

Alauddin Khan had a number of gurus at various points of his musical career, covering a wide spectrum: Fakir Aftabuddin Khan, Nulo Gopal, Amrita Lal Dutta, Lobo Saheb, Amar Das, Hazan Ustad, Ahmed Ali Khan and finally “Beenkar” Wazir Khan. His disciples were equally diverse in their musical forte. The list included his brother Ustad Ayet All Khan, son Ali Akbar Khan, daughter Roshan Ara (Annapurana Devi), son-in-law Ravi Shankar, nephews Khadem Hossain Khan, Mir Kashem Khan, Bahadur Hossain Khan, Yar Rasul (Phuljhari) Khan, grandsons Ashish, Dhyanesh and Khurshid Khan, and other disciples like Nikhil Banerjee, Timirbaran Bhattacharya, Vasant Rai, Rabin Ghosh, Pannalal Ghosh, Vishnu Govind Jog, Jotin Bhattacharya, Indranil Bhattacharya et al. Some of his lesser-known disciples trained from the Maihar band – Sanat Banerji (Sarod), Ranjit Banerji (Chandra Sarang), Shiv Balak Tiwari (sitar), Som Kartik Sharma, Shyam Bihari (sarod) graduated from orchestra to solo-artistes and moved into various allied fields, like teaching, broadcasting etc.

The Ustad’s daughter Annapurna Devi, often considered as the purest inheritor of the musical ideology of Alauddin Khan ( she was once described by Ustad Amir Khan as being “80 per cent of Ustad Alauddin Khan”) also carried forward the unadulterated Seni-Maihar parampara. Though herself a recluse (as far as public recitals were concerned), she was a renowned guru, and groomed an impressive array of shishyas. The line-up includes Ashish and Dhyanesh Khan, Shashwati Ghosh, Amit Hiren Roy, Sudhir Phadke, Daniel Bradley, Peter Van Gelder, Sandhya Apte, Headset Desai, Rooshikumar Pandya and Prabha Agarwal, all sitarists; Bahadur Khan, Jyotin Bhattacharya, Uma Guha, Basant Kabra, Pradeep Barot, Stuti Dey, and Suresh Vyas, among sarodists; and Nityanand Haldipur and Milind Sheorey, among flutists.

From Amir Khusru to Tansen and from Tansen to Alauddin, were watershed legacies shaping the very history of music in our country. Alauddin Khan, born into an unassuming family in a small village of Shibpur in Chittagong, became the biggest living legend and one of the brightest pole-stars of north Indian shastriya sangeet.

(The End.)

-By Sohini.

References:

Aashish Khan interview – Hyphen Magazine (http://www.hyphenmagazine.com/)

Ritwik Ghatak interview – Face to Face: Conversations with the Master 1962-1977, Cine Central

Nikhil Banerjee – My Maestro as I saw him (http://www.raga.com/cds/211/211text.html)

Mobarak Hossain Khan – Ustad Alauddin Khan, Monarch in the realm of music, New Age daily, Bangladesh, Sept 2005.

Rajiv Trivedi- Forging Notes: Maihar Band (www.omenad.net)

“Amar Katha” (My Life) by Alauddin Khan, Ananda Publishers, India.

*Scans from the preface of “Amar Katha”:

Related

This entry was posted on January 23, 2009 at 6:02 pm and is filed under চট্টগ্রাম, ফিরে দেখা, ব্রাহ্মণবেরিয়া, সংগীত. Tagged: Alauddin Khan, Ashish Khan, ঋত্বিক ঘটক, চট্টগ্রাম, ব্রাহ্মণবেরিয়া, chandra sarang, Maihar Band, Mobarak Hossain Khan, naltarang, Nikhil Banerjee, Ravi Shankar, saranga, Seni-Maihar gharana, Senia-Maihar, Siraju Dakaat, taalim, Tansen, Wazir Khan Beenkar. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

brishti aamaye said

চমৎকার গোছানো লেখা

বাঙ্গালদের সংগীত-সাধক নিয়ে অনেক অজানা তথ্য জানা গেল। 🙂

বিশাল এক ধন্যবাদ সোহিনীর অতি অবশ্যই প্রাপ্য!

Ritwik Banerjee said

Beautiful post, and really well researched. I had read Ustad Allauddin Khan’s biography when I was around 12 years old. That book remains one of the most influential books in my life till today.

By the way, I was wondering why you included Norah Jones’ picture here … even though she hails from Pt. Ravi Shankar’s family, her musical heritage is not even Indian in its true sense. Associating her to the Maihar gharana is something I personally do not approve of.

Sohini said

@Ritwik

You have raised a valid point, indeed, as it might be misleading and confusing to see Norah Jones’ photo amidst a bevy of Hindustani classical musicians of the present generation, sharing some connection to the Maihar Gharana (via the Guru-Shishya parampara).

So it is necessary on the author’s part to clarify that this gifted young singer-composer-instrumentalist has no connection to the Maihar gharana as far as musical genre and musical legacy are concerned.

I wanted to include her in the fourth gallery (the gallery of new faces of the current generation), primarily in a very broad sense of the terms ‘music’, and ‘legacy’. In fact, a disclaimer with regards to some faces in the gallery should be in place, in that I (being a non-technical person) do not know how true to the original (Alauddinesque) ‘Maihar gharana’ are the genre of some of the other young musicians pictured here. Their gayakis or individual styles may have been modified to some extent, as some have received tutelage from multiple gurus at various points of studenthood. All of them share a common musical heritage though, having been in long-time “taalim” with a guru from the Maihar Gharana.

Finally, the list in the galleries is by no means exhaustive.

Thanks much for pointing out this fine point and great to have you as a reader of our blog! 🙂

The Musical Legacy of Brahmanbaria « বাঙালনামা [Bangalnama] said

[…] Part 2 here.) Possibly related posts: (automatically generated)India Mourns Legendary […]

A K M Zahidul Islam said

অনেক ধন্যবাদ সোহিনী (মাফ করবেন,আপনার নামটা ঠিক লিখলাম তো?)। আপনার পরবর্তী লেখার অপেক্ষায় রইলাম। বলেছেন সংগীতে আপনি non-technical person, এটা হয়তো আপনার বিনয়। আশা করছি আপনার নিজস্ব দক্ষতাপূর্ণ বিষয়ে লেখা পাবো।

সোহিনী said

অনেক ধন্যবাদ, জাহিদুল! 🙂

Sarita McHarg said

This is the most rewarding and well-researched website I have found regarding the legacy of Baba Allauddin Khan. I am currently doing a PhD at Vikram University Ujjain MP, which is titled:

Padma Vibhusan Acharya Dr Allauddin Khan: The most influential figure in the history of North Indian (Hindusthani) Classical Music.

I thank you for this website, which supports my thesis in every possible way. I am also a student of Smt Joyas Biswas of Kolkata (Seni-Maihar Gharana), who is often referred as “India’s First Lady of Sitar”. As a young woman, my guru went to study at Maihar under the guidance of Baba Allauddin and eventually became a long term student of Pt Ravi Shankar. Perhaps she also should be mentioned in the long and illustrious list of “Seni-Maihar gallery – Alauddin’s best and finest”. If you agree, I can supply a photo for you. If not, that is OK too. Also, during my research, I have come to know there is some disagreement about the age of Baba Allauddin when he died (some say 110, others say 91) about which we can share notes if you are interested. Thank you once again for your fantastic website.

Sarita McHarg, Ujjain MP.

PS: How can I access the The Musical Legacy of Brahmanbaria Part 1?

Sohini said

Sarita,

Glad to know that the write-up is interesting and of some use to you. 🙂 How did you find us?

We would like to invite you to write for us too, on Baba Alauddin Khan. You might be able to cover aspects that were missed in our articles on the maestro.

Please let us know more about Smt Joya Biswas, and email us a photo of her, too (bangalnama at gmail.com, and we would be happy to include her in the Seni-Maihar gallery. Do you have any reference on the debate over the controversy over the age of Baba Alauddin Khan when he died? I am intrigued to know more about this.

The other article (part one) can be found in the “Music” section.

Look forward to hearing from you. And hope you write for us too! 😀

Sarita McHarg said

Dear Sir,

I am sorry not to have written earlier than this but we have been out of station for the last 5 weeks and I did not have any opportunity. Regarding the age of Baba Allauddin Khan, you may refer to Chapter 16 of USTAD ALLAUDDIN KHAN AND HIS MUSIC, by Jotin Battacharya, published by B. S. Shah Prakashan, 1183 Pankore Naka, Ahmedabad – 380 001 INDIA. According to the Author (who was a student of Baba) it is relatively certain that Baba was born in 1881 (see page 113) and he died on September 6th 1972. By this calculation, he lived to the age of 91 years, not 110. Jotin Battacharya was a disciple of Baba’s and lived at his Maihar residence from 1949 to 1956. He was requested by Baba to write the Biography. I will write more and send a photo of my Guru-maa Joya Biswas soon. Respectfully yours,

Sarita McHarg

bangalnama said

Thanks much for the information, Sarita!

Sarita McHarg said

Dear Sir,

The final word on the subject of Baba Khan’s birth year comes from American musician and author Peter Lavezzoli who, in his book, The Dawn of Indian Music in the West: Bhairavi, refers the reader to the Oxford University Press publication, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, for the accepted academic view.

“Ustad Baba Allauddin Khansahib was born in Shivpur, East Bengal, in the same town where his son Ali Akbar would be born in 1922. Although his birthday was always observed on October 6, the exact year of Allauddin Khan’s birth has remained a mystery. With his life and achievements reaching an almost mythic status, it is easy to see how his birth date and lifespan would be yet another matter of legend. What is certain is that the Indian government and village of Maihar officially celebrated Allauddin Khan’s centennial birthday on October 6, 1962. This would mean that when Khan passed away on September 6, 1972, he was 109 years old. But this would also mean that Allauddin Khan was almost sixty years old when Ali Akbar Khan was born in 1922 (possible enough), with Ali Akbar’s mother in her late forties or early fifties (far less likely). It is much more likely that Allauddin Khan’s age was exaggerated by approximately twenty years. Historian Martin Clayton, in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, has produced the more plausible year of 1881.”

Reference: The Dawn of Indian Music in the West, Chapter 4, pps 67–68.

Sarita

সোমনাথ মুখোপাধ্যায় said

ব্রাহ্মণবাড়িয়া ও বিশ্ববরেণ্য সঙ্গীতজ্ঞ বাবা আলাউদ্দিন খাঁ এবং মাইহার ঘরানার অনেক দিকপাল উস্তাদ ও পন্ডিতদের সঙ্গে সঙ্গে আরেক বিরল ব্যাক্তিত্বের কথা না লিখে পারলাম না। আমি তাঁকে ডাকতাম হেমেন জেঠু বলে। দেশপ্রিয় পার্কের কাছে প্রিয়া সিনেমা হলের বিপরিতে ১৪০বি রাশ বিহারী এভেন্যু ‘হেমেন & কোং’ এর ছোট্ট দোকান। একই জায়গার আদি বাসিন্দা হওয়ার দরুন বাবা আলাউদ্দিন খাঁর ভাই ওস্তাদ আয়েৎ আলী খাঁর কাছেই হেমেন বাবুর সঙ্গীতে তালিম এবং একই সঙ্গে সরোদ বানানোর শিক্ষাও। শুধুমাত্র সরোদের ‘মাইহার প্রোটোটাইপই’ নয় এমনকি ওস্তাদ হাফিজ আলী খান সাহেব / ওস্তাদ আমজাদ আলী খাঁ সাহেবের সরোদের মডেলেও হেমেন বাবু বানাতেন। সারা বিশ্বে ছড়িয়ে থাকা সমস্ত নামী দামী সরোদীয়া হেমেন বাবুর বানানো বাদ্যযন্ত্রেই বাজিয়ে থাকেন। উস্তাদ আলি আকবর খাঁ, উস্তাদ আমজাদ আলী খাঁ এবং এই দুই ঘরানার অজস্র সরোদীয়াদের সুর হেমেন বাবুর বানানো সরোদ থেকেই বেরিয়ে থাকে। দেশে এবং বিদেশে অনেক উস্তাদ ও পন্ডিতদের কাছে হেমেন্দ্র চন্দ্র সেন নামটি বিশেষ ভাবে সমাদৃত।

২রা জানুয়ারী ২০১০ এ ৮৭ বছর বয়সে হেমেন বাবু পরলোকগমন করেছেন।

bangalnama said

@সোমনাথ

হেমেনবাবুর সম্পর্কে লেখার জন্য আপনাকে ধন্যবাদ।

Tanim Hayat Khan said

Thanks Shomnath babu for remembering Hemen Jetha……I had the opportunity to meet with him once and then he recalled few stories of my father Mobarak Hosssain Khan’s childhood..

Will write more.

Tanim Hayat Khan

(Grandson of Ustad Ayet Ali Khan)

Nupur Das said

Mr. Tanim Hayat Khan,

In this context, mentioning a book in Bangla compiling some of the Ustad Allauddin Khan’s letters can be worthwhile. The book was written and edited by your father Mobarak Hossain, published by Bangla Academy, Dhaka. It is an invaluable treasure for the music-lovers.

Tanim Hayat khan (Rajit) said

Yes, Ms Nupur Das, I do have a copy of the text book.

But I would like to ask Ms Sohini (the writer of this article), I cannot see my name in tree. It may be I live in Australia since 2003? I am a full phased Sarodia. Another thing. I can see three children of Raja Hossain Khan. But they are not musician. May be as a hobby. But not like what we do. They are my brothers, so offence at all. I was just trying to find why my name was there (thought you may not that I’m a musician too, then I thought why Raja Hossain Khan’s three sons names are there then).

Could you please advise?

You can google my name or search in You Tube (by my name) to get understanding about my musical involvement, even though I live in Sydney.

I also have another post two years back . I haven’t received any reply of that too (About my grandfather Ustad Ayet Ali Khan) and my Jetha Ustad Bahadur Khan).

I can be contacted on tanim@live.com.au

Kind regards,

Tanim Hayat khan (Rajit)

adaap said

Sarthok hok Manob Jonom amar. Eai Hujuk sorboshyo dhandabazir juge eai cyber jongole Eai rokom ekti site je ajo ache—- kaal’o thakbe….. bhebe gorbo hoy. Simply proud of it . One Day One time our vision must be meet in here.

Opekhyea achi……

Sarita McHarg said

Dear Sir,

I have finally completed my PhD thesis on Dr (Baba) Allauddin Khan. You may find excerpts from the thesis on my website at;

http://www.saritamcharg.com/

via the “Baba Khan — Book extracts” link. The thesis will be published in book format some time in the coming months. I hope this is of interest to you. Best wishes,

Sarita McHarg

Kasturi said

Sarita, Delighted to hear about the upcoming book. Look forward to reading it! Well done, and best wishes. 🙂

Dr Saikat Chowdhury said

Wonderful effort.

Please please include Sarod rani Padmabhushan Sharan Rani…a Legend of Sarod in the tree.

She is a pride of the Indian Classical Music….

Tanim Hayat Khan said

Well researched writing Sohini, but did you have a final check with my father? I can see few discrepancies here and there, particularly the familiy tree is missing few important names including myself. …….

I’m extremely connected with my family all over the world including our relatives from Shivpur, to India to USA and so forth.

But I really appreciate your writing about our Gharana. But I believe my Grandfather Ustad Ayet Ali Khan and my Chacha Ustad Bahadur Khan were completely ignored. Not feeling well about this as these two are the integral part of Seniya Maihar Ghorana.

Feel free to contact with me if you need any further assistance or clarification from me.

Thanking you again for such a report. Good initiative.

Tanim Hayat Khan

(Son of Mobarak Hossain Khan, Grandson Of Ustad Ayet Ali Khan)

Jeet said

Dear Sohini,

Thanks a lot for this wonderful article and your painstaking research.

Love & Regards

Jeet

Tanim Hayat khan (Rajit) said

Yes, Ms Nupur Das, I do have a copy of the text book.

But I would like to ask Ms Sohini (the writer of this article), I cannot see my name in tree. It may be I live in Australia since 2003? I am a full phased Sarodia. Another thing. I can see three children of Raja Hossain Khan. But they are not musician. May be as a hobby. But not like what we do. They are my brothers, so offence at all. I was just trying to find why my name was there (thought you may not that I’m a musician too, then I thought why Raja Hossain Khan’s three sons names are there then).

Could you please advise?

You can google my name or search in You Tube (by my name) to get understanding about my musical involvement, even though I live in Sydney.

I also have another post two years back . I haven’t received any reply of that too (About my grandfather Ustad Ayet Ali Khan) and my Jetha Ustad Bahadur Khan).

I can be contacted on tanim@live.com.au

Kind regards,

Tanim Hayat khan (Rajit)

(Grand son of Ustad Ayet Ali Khan, and Son of Mobarak Hossain Khan)

Dr Bibek Gupta said

Dear Sohini,

Thanks for this wonderful article enriched with treasured facts about which I was completely ignorant about. This gives an insight to the contribution of Maihar gharana to Indian Shastriyo sangeet. I am a devotee of Pandit Nikhil Banerjee and took the liberty in posting Panditji’s memoir into our facebook forum. We will look forward towards you to join our forum “Nikhil Banerjee” as a member in Facebook. My heartfelt thanks for your gem of an article!

Dr Bibek Gupta

bibekgupta@yahoo.co.uk

Major Energy said

Major Energy

The Musical Legacy of Brahmanbaria – II « বা ঙা ল না মা